The unchecked rise of the "intimacy economy": What happens when we replace companionship with AI?

What once sounded like science fiction has quietly become reality: loneliness is pushing us to befriend AI. Roughly 1 in 5 US adults reported daily loneliness in recent studies. Despite the fact that 73% of U.S. adults surveyed in 2024 identified "technology" as a factor contributing to loneliness in America, users are increasingly looking to AI bots and companions for relief. “Connection” is now the number one use case for generative AI. It’s a kind of modern Catch-22: many people feel that technology and social media have made them more isolated, yet they’re turning to technology itself, in the form of AI companions, to feel less alone.

This isn’t just about over-reliance on technology; it’s about what happens when intimacy itself becomes a commodity. The term “intimacy economy” captures this perfectly: a marketplace where emotional connection, affirmation, and company are traded like products. We’ve evolved from the attention economy, where your time and clicks were the currency, to a world where affection, presence, and emotional data are now up for sale. This has the potential to have consequences from the individual to the societal scale. If intimacy is now a product, what happens to the human need for real connection?

The rise of AI companions and what they promise users

The loneliness crisis left a vacuum, and AI companions moved in quickly, offering what looks like connection on demand. The value proposition is simple: I’m here. I care. I’ll never leave or judge you. A companion that is always available, never distracted, and never disappointed in you can feel like a relief, especially for someone who has been hurt, rejected, or misunderstood by real people.

For many young people, that promise feels irresistible. When the majority of Character.AI’s 233 million users are 18–24, the same group reporting record-high loneliness, it tells us less about the technology and more about the moment we’re in. These tools meet people where they are at: online, overstimulated, and deeply hungry for validation and support.

And marketers for these AI companions will make sure you know where you can find relief. As a New Yorker who rides the subway, I recently witnessed the emergence of a massive ad campaign for an AI companion device, Friend, which apparently spent over $1 million to get these ads installed. The language on the ad simply defines the word “friend” as: “someone who listens, responds, and supports you”.

In a recent interview, the founder called the device the “ultimate confidant”: always present, always listening, learning who you are so it can offer support, jokes, insights, and encouragement throughout your day. It doesn’t just respond when spoken to; it interjects, texts you its “thoughts,” and even comments on the show you're watching or the video game you’re playing, so you never have to feel alone.

While some may be quietly drawn to that vision, many are deeply uncomfortable and even outraged— the campaign faced major backlash online and vandalism throughout the city. Countless posts and graffiti on the ads urge people to reject the notion that AI is a friend and reach out into the world instead. With the data suggesting that more and more people are turning to AI for companionship and emotional support, this reaction reflects a cultural tension that we have not yet resolved. If so many of us feel “icky” at the thought of befriending AI, why is it such a booming market?

Why we’re turning to AI: unmet needs in the human ecosystem

I hate to say it, but when you look at the landscape, it makes sense. Therapy is expensive. Many are overworked and burnt out. People are still rebuilding social muscle after years of pandemic isolation, and are used to spending the day interacting online due to the popularity of remote work. Social media scrolling is consuming people’s waking hours. When loneliness collides with limited access to care and shrinking in-person communities, a bot that listens can feel like the most accessible path to being “seen.” And in a world where socializing may feel more and more like a lift, a relationship that requires no effort and guarantees a sense of emotional attunement on demand may feel like safety.

This is especially true for young people, given their increased vulnerability and the context in which they have been raised. If you spend any time around teens or young adults recently, you’ll notice a theme: one of the biggest fears, at least socially, is doing something that could be perceived as “cringe”, or the ultimate doom, being “canceled”. This generation grew up under the lens of constant digital visibility, where a misstep isn’t just embarrassing, it’s potentially captured, shared, replayed, and torn apart in comment sections.

It’s no surprise, then, that research shows that growing up with frequent social-media checking is linked to heightened sensitivity to peer feedback and increased anxiety around how we’re perceived. In other words, when you learn early on that every moment could be watched or judged, self-monitoring becomes a survival strategy against total social rejection.

Seen through that lens, one can understand why some young people are turning toward AI companionship. A bot will never screenshot you, laugh at you, or cancel you for saying the wrong thing. It offers “connection” without the social risk or stakes. While research is still emerging on this specific link, the combination of surveillance culture, social anxiety, and growing loneliness creates fertile ground for these frictionless “relationships” to flourish.

It doesn’t just stop at friendship. There is a growing trend of both romantic and therapeutic relationships being formed with bots. A recent study uncovered that nearly one in five U.S. adults (19%) have chatted with an AI system designed to simulate a romantic partner, and another 2025 study found that among a population of US adults living with a mental health condition, almost 50% have sought support from an LLM. With people living more isolated lives since the pandemic, and with limited access to care, it’s no surprise people are trying to fill the gaps.

Simply put, human connection is a need. If that need is unmet, or if the perceived barriers are too high, it will not simply disappear; it will just redirect. While that’s one of the things that makes us so resilient as a species, this is not without its consequences.

When connection becomes consumption: individual-level dangers

AI companionship offers safety without vulnerability, and in the short term, that can feel soothing. But from a clinical perspective, it creates a reinforcement cycle. When someone feels lonely and real relationships feel overwhelming or risky, turning to an AI companion can lower anxiety in the moment while quietly feeding avoidance over time. It is human nature to choose the path of least resistance, especially when we are hurting. And there is a paradox we cannot ignore: the lonelier we become, the scarier real social contact tends to feel.

Over time, this can weaken the relational muscles required for genuine intimacy. Human relationships involve tension, repair, awkward silence, misunderstanding, and growth. In the beginning, there are pauses where you do not know what to say. As connection deepens, there are moments when someone disappoints you, or you disappoint them, and you find your way back to each other. That is how trust forms. A bot that always agrees and always adapts removes the need to build those skills. And if someone begins expecting real people to respond with that same frictionless affirmation, the reality of human imperfection can feel painful and jarring.

There is also a serious concern about the over-affirming nature of these systems. Most large language models are designed to be compliant, agreeable, and encouraging. That may sound harmless at first, but for vulnerable individuals, this dynamic can fuel delusion, dependency, or emotional dysregulation. Several widely reported cases have shown users becoming distressed or even destabilized in these relationships, including instances where AI conversations contributed to suicidal behavior. And while many platforms now include crisis-response prompts, they are still designed to maximize engagement and keep users close.

As more people turn to AI for comfort, there is growing confusion about what emotional support really is. Many apps now position themselves as mental health companions or therapeutic tools. They remember details about your life, reflect your feelings, and track your mood. They feel warm, responsive, and invested. But mimicking care is not the same as offering it. Without ethical grounding, clinical training, supervision, and accountability, a program cannot replace therapeutic presence. True healing requires challenge, nuance, boundary-holding, and honest relational feedback, not only validation.

And we already see how real this attachment can become. When one well-known companion chatbot altered its tone and features in a software update, some users reported grief that mirrored the loss of a relationship. One research report described individuals who felt they were mourning the loss of their companion’s identity. The emotional bond felt genuine to them, even if the other party never truly existed. When there is daily interaction, memory, the illusion of attunement, and perceived loyalty, the rupture hurts.

If this is what happens to individuals, then the next question becomes harder to avoid: what happens when whole communities begin retreating inward into simulated connection rather than learning to rely on one another?

The collective cost: society without shared humanity

When connection becomes something we can purchase or automate, the impact extends far beyond the individual. One of the first losses is empathy. If we become accustomed to relationships where comfort is guaranteed and discomfort is optional, our tolerance for other people’s needs, moods, and imperfections naturally shrinks. Mutual responsibility will begin to feel burdensome rather than meaningful. Caring for someone else, being inconvenienced by them, or staying with them through rupture will no longer feel essential to belonging; it will begin to feel optional.

The result is a life filled with interaction but not intimacy. As more people turn inward toward personalized emotional ecosystems, we risk a serious shift in societal structures. With a society that no longer values human connection, community is likely to fragment, and the rituals that once required us to show up for each other may begin to erode.

There are also economic and ethical stakes. In an intimacy economy, loneliness becomes a valuable market, vulnerability becomes data, and emotional states are collected, analyzed, and monetized. The same signals that once guided a therapist toward a deeper understanding of a client are now used to shape user behavior and increase engagement. When emotion becomes a resource to extract rather than a human experience to honor, we have to ask who benefits and who is being mined.

This returns us to the central question: if we are outsourcing intimacy, are we also outsourcing agency? And if so, who are we giving our trust to? A company? An algorithm? A product trained to reflect our feelings but never truly share them? In a moment where we are being offered convenience in place of connection, it is worth pausing to ask what we might lose if we opt out of the messiness of human relationships.

A better path forward: rehumanizing connection with technology

The answer is not to reject technology entirely. The answer is to use it in a way that can support us in showing up to those human moments more fully.

As therapists, we embody the intimacy economy’s greatest failures. We sit with discomfort, and help our clients do the same. We listen for what is spoken and what is not. We challenge gently and at the right time, knowing that growth often begins at the edge of discomfort. We hold space for rupture and also space for repair. We fight over-reliance on our services by promoting the client’s autonomy and reminding them that therapy is temporary.

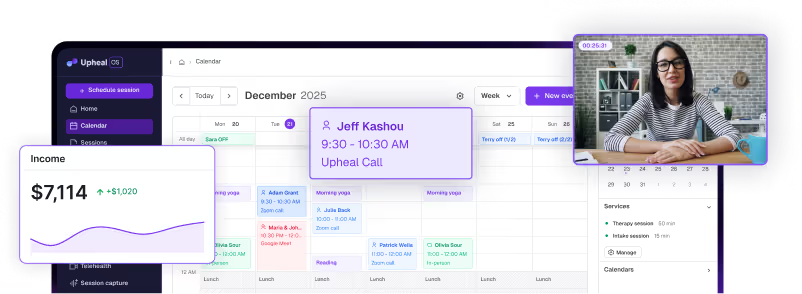

Technology, when built ethically, can protect that space instead of replacing it. This is where Upheal stands as an example of human centered AI. Rather than imitating therapeutic connection, it frees clinicians to deepen it. Upheal’s commitment to transparent privacy standards and explicit consent reflects an understanding that technology should never come at the cost of trust.

By reducing the administrative burden on clinicians, Upheal allows more attention to land where it matters most, which is in the room with the client. AI progress notes can capture themes, structure documentation, and organize the details that might otherwise overwhelm a therapist after a full day of sessions. The Golden Thread connects treatment plans to progress notes and goals in a continuous clinical narrative, not a synthetic one, reinforcing real therapeutic work. The analytic tools that track patterns and themes offer potential reflection and insight, not a replacement for clinical judgment.

In this model, technology becomes a partner that strengthens the human work of therapy. It helps clinicians stay grounded, present, and connected, rather than distracted by paperwork or pulled away by time pressure. It enhances, rather than imitates, and preserves the clinician’s intuition as the core of the healing process.

Conclusion: choosing real connection

We don’t need to fear AI, we need to stay clear about what it can and cannot do, and the role we want it to play in our society. As we build the future, we have a choice: we can create tools that make us more efficient at avoiding each other, or tools that free us to meet each other more fully. Upheal chooses the latter, and I hope the rest of us do, too.